International Artist Mark Dion Introduces a Deeper World Viewpoint to Students

A behind-the-scenes look at HONS/ARTS 3555

In HONS 3555, also known as ARTS 3555, we experienced a class unlike any other. In this class, which had a highly experimental design, we met once a week for two and a half hours to discuss whichever topics were crucial that day. We went on a total of 22 field trips throughout the semester, which included a visit The Possum Trot Auction, thrifting days, a riverboat ride on West Point Lake, and a private tour of the Columbus Museum archives. These field trips were meant to aid us in helping the internationally renowned artist, Mark Dion, with his curiosity cabinet that he was asked to build for the Columbus Museum. We learned about the scientific, economic, social, and historical implications of the Chattahoochee River and surrounding area, and we eventually began to spin a conducive story around it all that found its way into physical artwork.

My first week with Mark was one that really opened up my mind to the endless interpretations that can coexist for one particular item or idea. My time with Mark and this class has taught me to see how nearly everything in life and on this world has the same multiple facets and multiple perspectives. It is all complicated, and in that, it is all interconnected.

At the beginning of the week, in preparation for meeting Mark, I was not quite sure what to expect. An eccentric, successful artist? An intelligent, linear-thinking professional? Perhaps, a rebel with a cause? As I began to spend time with Mark in different settings with different audiences, I realized that he, too, has multiple facets and that he is, in fact, all of those things and more.

For example, my first time meeting Mark was in a classroom setting with the 15 of us who are in that class and our professor, Mike McFalls. In this small, intimate situation, we all introduced ourselves and had a scholarly discussion with Mark with little dashes of personal quips thrown in. Afterwards, we went out in public with Mark to eat at Barberitos. This provided a new setting with a new atmosphere, and thus, we saw a new facet of Mark. He was less focused on the art and ideas we talk about in class and instead exhibited a personal, familial personality that we could all easily get along with.

The multiple facets of Mark extended even further with every event that I attended.

At his lecture at the Columbus Museum, Mark was put on a stage with an audience of art professionals, business professionals, and other influential people in the community. With this came yet another facet of Mark, one that is simultaneously professional and calculated, comical and amiable. This “in-the-spotlight” Mark certainly made it clear to me how experienced and well-versed he is in both his profession and life in general. Mark showed the audience examples of his work that he had done around the world, and I learned a lot about both what he had done and about the process of art and research. I had not realized previously that Mark had done so much in other countries and on such a large scale. I did not realize how meticulous the process of building the curiosity cabinet was. I also had not realized that curiosity cabinets are actually an old, prominent idea in the art world and that Mark is bringing them back to life rather than creating one for the first time.

On another trip, during the riverboat ride on West Point Lake, we turned an eye to the scientific facet of the Chattahoochee River, and with that, Mark displayed his scientific mind.

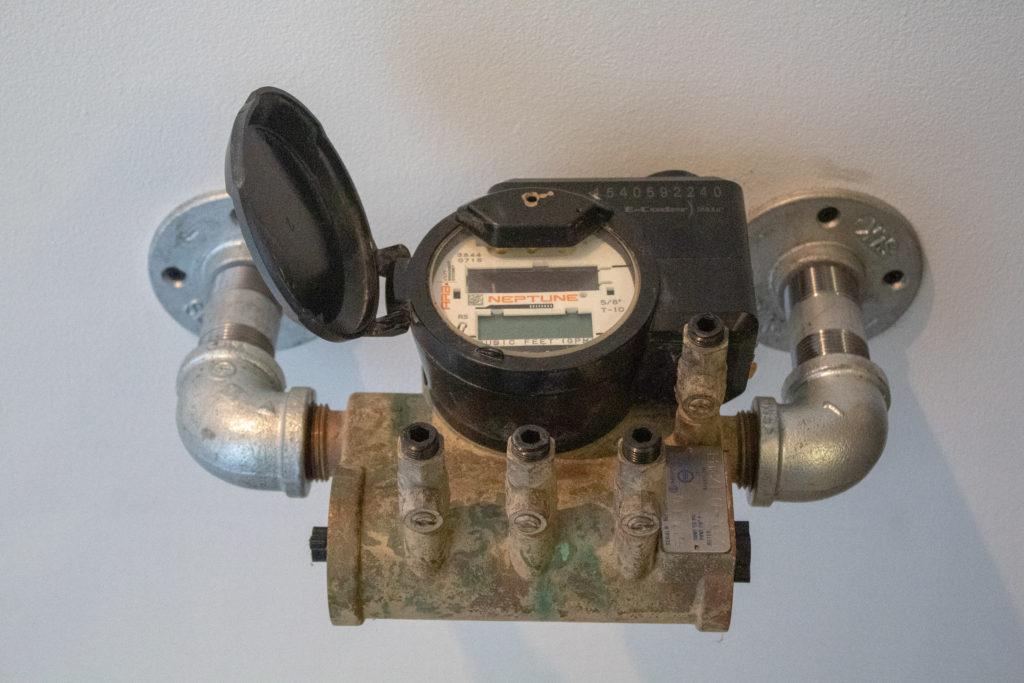

We employed the help of CSU Science Professor Troy Keller to use a tool to measure the temperature and oxygen levels at different depths in the lake. We learned that the shapes of West Point Lake and other lakes on the Chattahoochee are unique in comparison to other lakes because they are manmade, and that gives them their characteristic spindly shapes that resemble paint splatters. Additionally, I witnessed how disciplines can overlap. In the process of scientific research on the lake, one can also do cultural or anthropological research. By studying the mud from the bottom of lakes, you can learn about the different civilizations that lived there and when they lived there, based on the kinds of pollen found at different depths.

Through all of this new knowledge, all of the man-made objects found by Mark and his team on the shores of the Thames, the shape of West Point Lake, and even the types of fish that can survive near the dams, I have really noticed how much of an impact human presence has had on everything deemed as “Nature.”

This makes me think of the reading we did at the beginning of class about the nature of “Nature,” and I have come to determine that humans and nature are interwoven to the point that we could never untangle ourselves from it. Humans are, in fact, a part of nature rather than a separate entity. Whether we were always a part of nature or whether we bullied our way into it, I have yet to determine.

Because everything has multiple interpretations and meanings, as I have come to realize, what are the facets of being human? What are the facets of nature, and do those facets only exist because humans exist? Are the words and concepts that we use to understand Nature simply man-made constructs that do not denote reality? If humans hadn’t evolved to essentially take over the planet, would there be a meaning to Nature at all, or would there even need to be a meaning?

For Dion’s second visit to Columbus, the class went on a myriad of outings.

Of all of the trips we went on, two, in particular, stood out to me. These were the tour of art collectors Marc Olivie and Marleen De Bode’s apartment and our visit to Oxbow Meadows. With these, I got a glimpse into two types of living/working that I otherwise would not have ever had a chance to experience.

At Marc and Marleen’s apartment, I was having a stressful day, and I was admittedly not in the mood to have to do anything. But the moment I stepped into that apartment, I felt as if I had walked into a dream, another dimension, or onto a cloud that floated above the rest of the world, where the only things that mattered were matters of culture. Their apartment was very aesthetic, minimalistic, and modern. Surrounded by white, concrete floors and high, industrial ceilings, I felt transported to a place of peace and serenity. My first instinct was to not touch anything because it was all so perfect, clean, and crisp — that my mere presence was a disturbance.

As we talked with Marc and Marleen, I slowly realized that this was not a dream or a pristine place, but it was a home. A real home that real people live in. This beautiful little enclosure of peace is something attainable. That was a very interesting revelation, because until I walked across that threshold, I had not experienced a place or life like that before. Seeing Marc and Marleen doing what they love, surrounded by what they love gave me hope.

From the art perspective, it was certainly interesting to view art pieces from the point of view of a collector rather than in a museum. That made these art pieces personal. It gave them another layer of meaning that otherwise would have never existed. These pieces of art were being enjoyed and used for a specific reason, for a specific person who has unique experiences, emotions, and memories.

A conversation consists of an encoder and a decoder. The encoder places the message within the words, which in this case is a piece of art, while the decoder then takes that message out of the words. When it comes to art, the decoder takes the message out that means the most to them. When the art belongs to an individual, then it takes on the meaning that that individual decodes out of it, making it unlike any other piece of art in the world.

At Oxbow Meadows, we collected samples of various plant and bug life in the area. We were able to use waders, nets, and kayaks in this process, and we harvested little organisms from the muck that we scooped up out of the marsh. All of this was truly scientific field work. I had to maneuver in a kayak in order to scoop up a zooming, elusive water bug with a plastic bag, a simple task that sounds relatively normal, but a task that I would have never found myself having to do. Under the guidance of the scientists we worked alongside, I caught a glimpse into the behind-the-scenes, everyday aspects of the science side of nature.

All of these experiences helped us to make our individual art projects as well, which were displayed in the Bay Gallery in the Corn Center under the show name of [Man]ipulation. For my partner Dalton Tanner and I’s project, we decided to hang a globe with a noose made of plastic bags and paint “I=PAT” behind it in large, bold font.

Today, I am one of more than seven billion people walking around planet Earth, compared to the two billion in 1900. I = PAT is an equation that expresses the idea that environmental impact (I) is the product of three factors (population (P), affluence (A), and technology (T)) as a way to calculate the impact of humans on the environment. These letters are simple but stand for very large and impactful ideas, which is why we decided to illustrate this by displaying the earth being hanged by the weight of the human impact. All materials used are man-made materials most often found in landfills. The globe and letters were hung using a braided noose made of plastic bags to represent the way in which the human impact is weighing down the earth and will continue to suffocate it if the right side of the equation continues to grow exponentially.

Artworks Created by the students

Photos by Raylyn Ray