Redlining: the stealthy segregation that continues to plague Columbus

Columbus is a historic city, and like many American cities, it still bears the scars of discriminatory policies from long ago. One of these policies is redlining, a practice beginning in the 1930s which denied home loans to anyone who lived in predominantly Black neighborhoods. This effectively shut Black communities out of the middle class and perpetuated segregation. This would end up affecting the wealth and health of these communities for generations.

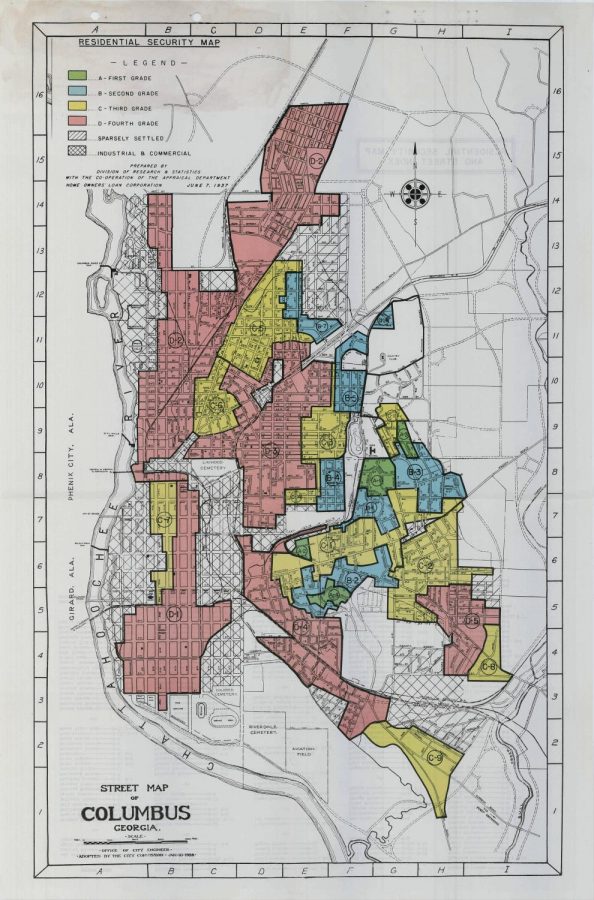

Redlining was enforced and carried out using color-coded maps, distinguishing whether an area was “desirable” or “hazardous” along with a graded rating from A to D. On a preserved redlining map of Columbus from Mapping Inequality, one area with a C rating includes the caption, “There is some Negro property located along the northeast side of Cusseta Road and east side of Lumpkin Road which should carry a D grade rating.” These “low-rated” areas were colored red.

Areas with a “low” rating would not be guaranteed loans from banks. As the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation stated at the time, “responsible” lenders would “refuse to make loans in these areas [or] only on a conservative basis.”

This ensured that Black people could not become homeowners at nearly the rate of their white counterparts. And despite the fact that redlining is no longer an officially accepted practice, its effects continue to harm the same populations it initially targeted.

“Housing is how people generate money in America – you buy a house, and the money you make on the house selling it you invest, or you pass it down,” said city planner and CSU alumnus Scott Berson. “For a long time, Black people could not do that by law. And those effects along with general prejudice have kept Black neighborhoods poor for generations and generations while white neighborhoods have been allowed to compound their wealth growth over time based on their previous wealth.”

On “The Amber Ruffin Show,” the titular host asked how many viewers live in or know someone who lives in a home that has been passed down within the family.

“That’s called generational wealth,” Ruffin explained. “Home ownership is the number one driver of wealth in America. […] You can use a home to pay for college or start a business or, you know, not be homeless. But if you look at almost any major American city, most of the formerly redlined areas are majority Black and low-income.”

Ruffin went on to explain that banks continue a form of redlining to this day. “Homes in majority Black neighborhoods are valued at 25% lower than homes in white areas, even when the crime rate and the neighborhood amenities are exactly the same. And because school funding is based on home values, the average non-white school district receives $2,226 less per student than a white school district.”

Because crime is directly linked to wealth and education, police tend to patrol these areas more frequently. As a consequence, Black people are 3.5 times more likely to be arrested for drugs, despite there being no difference in the rate of drug use between white and Black people.

Redlining has also led to a literal temperature rise in Black neighborhoods.

“In general it’s caused horrific problems for generations, in terms of affordable housing and wealth-building but also general investment,” said Berson. “For example, redlined neighborhoods are literally hotter temperature-wise today than others because of landscaping disinvestment in trees.”

One study on this particular subject found that “94% of studied areas display consistent city-scale patterns of elevated land surface temperatures in formerly redlined areas relative to their non-redlined neighbors by as much as 7 °C.” Western and Southwest cities like Columbus showed the greatest difference.

Berson concluded, “So while redlining as an actual practice is long gone history, the effects of it have set Black neighborhoods back decades.”

(She/her) Ashley is a theatre major who loves to focus on issues that concern the community of Columbus. She graduated from CSU in Spring 2021,

Geneva Turner • Oct 18, 2021 at 11:17 am

On reading your thoroughly researched article, I wanted to rejoice. Finally, information in black and white that those of us who are affected by this pervasive zoning scheme in the USA for decades. Thank you for being very factual in your writing about this ongoing travesty.

Timothy Wilburn • Mar 9, 2021 at 7:08 pm

I love that you wrote on this. I’m not from Columbus so it’s very interesting to put what I see with what has happened in the past. Great Job!