Et in Arcadia Ego: A Journey to Oxford and back

A cynical graduating senior reflects on her time as a visiting student at the University of Oxford.

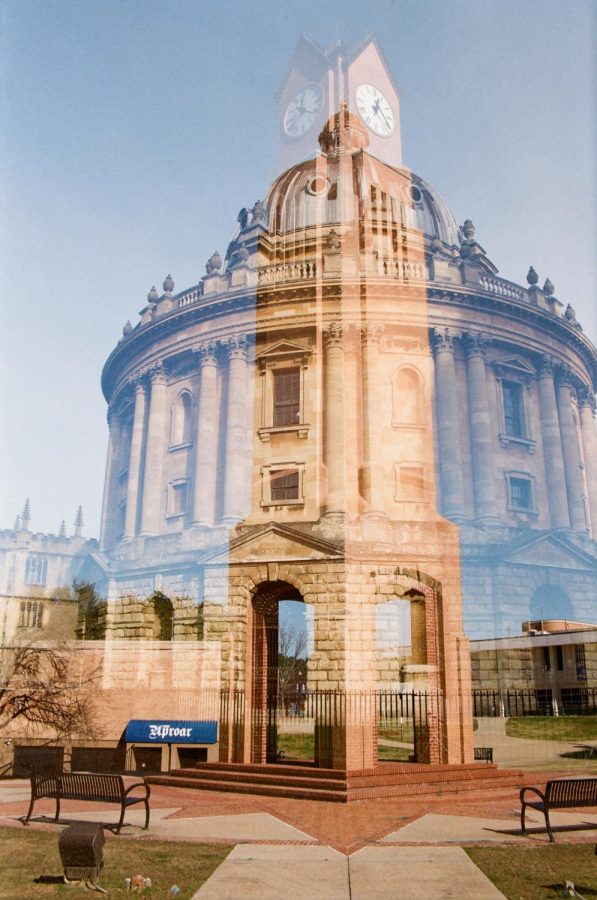

Kodak Gold 200 double exposed film photo featuring the CSU Clocktower and Oxford University’s Radcliffe Camera.

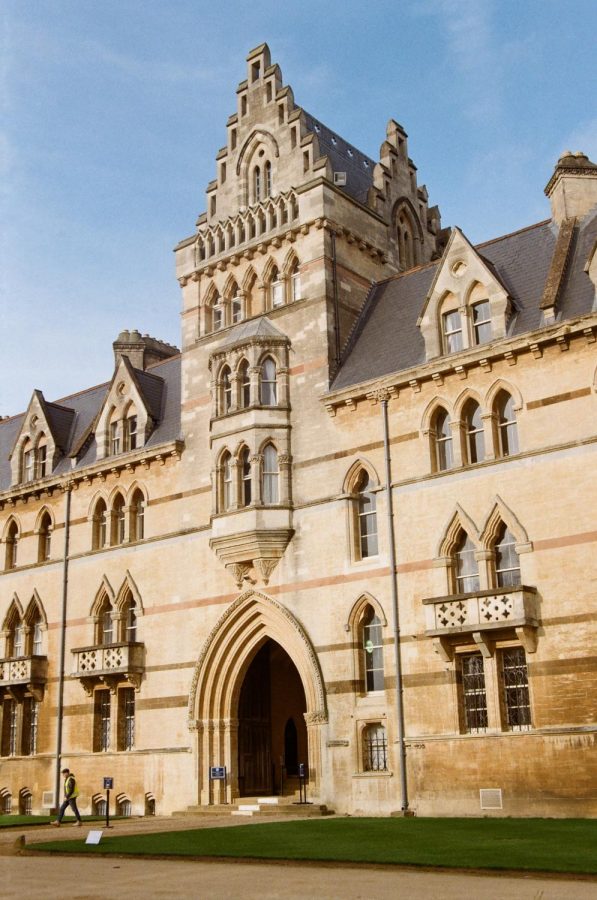

For three terms as a visiting student at Oxford, I studied in the city’s “spacious and quiet streets…her autumnal mists, her grey springtime, and the rare glory of her summer,” to borrow Evelyn Waugh’s description of the city from his novel Brideshead Revisited, the beginning of which famously takes place at Oxford. My time at Columbus State University provided me with a solid foundation on which to build my educational career. Oxford became my intellectual playground, with its numerous museums, beautiful architecture dating from medieval times onward, and its unique tutorial system. Nearly every day, I rushed down Woodstock Road on my bright orange Dutch bicycle towards the city centre’s dreaming spires, against the cold winds, which made me feel like a main character from Brideshead. When I wasn’t studying or writing an essay in one of Oxford’s gorgeous libraries, I sought out the joys of the outdoors; I often found myself experiencing Burke’s idea of the Sublime in the city’s picturesque natural landscapes. It was in those days at Oxford that I felt most inspired, and I had never experienced such personal and intellectual growth in such a short time frame.

Whenever someone asked me what it was like to be in Oxford, I always responded with another question: “What better place to study English literature than Oxford?” Living in the city where so many great intellectuals studied and wrote made me feel as if I was carrying on a sacred tradition. The authorial heritage that surrounded me served as an incredibly inspiring backdrop to my studies. I never grew tired of thinking of which people had preceded me. I was even able to view primary sources from some of my favourite authors up close.

Most importantly, the one-on-one tutorial system at Oxford is what allowed me to develop the most. I have considered entering academia for some time now, but my tutorials cemented it in my head. My tutors constantly encouraged me and challenged me to go further. They saw promise in me, and I hold their praise on imaginary plaques in my mind. One of my tutors once told me that they could easily see me becoming an expert in the 19th century. One of my other tutors, an early modernist, told me that I “belong at Oxford,” and that I always “provide a new insight into Shakespeare,” which are the highest compliments to receive from someone who is an expert on Shakespeare. I’ve always struggled with severe imposter syndrome, so receiving this praise helped boost my confidence in my abilities. My tutorials at Oxford allowed my mind to expand in ways I never thought imaginable, and as my time there comes to an end, I look forward to making nuanced approaches in whatever I study.

I began my undergraduate honors thesis titled “‘Mine Own Country:’ Christina Rossetti and the Italian Risorgimento” during the end of my first term at Oxford. The thesis analyzed the Victorian poet’s relationship and sentiments for the 19th-century socio-political movement that aimed to unify the regions of the Italian peninsula into one country. Academics tend to ignore Rossetti’s political sympathies and instead focus on the politics of her male family members. I believe this is because she is a woman and the “feminine” nature of her biography and œuvre; they both seem to solidify what appears on the surface to be a “meek” woman. Although the literature has so far neglected it, her works reflect her political involvement and sentiments. Indeed, we cannot ignore the politics of someone whose family was so involved in the politics of her time. Because there is so little research on this specific relationship, I struggled to write my thesis, but being at Oxford helped me greatly because I had access to so many resources related to my research. I felt as if I were at the beginning of a long intellectual path, and I could easily see myself expanding my undergraduate thesis into an academic book someday. Writing my thesis also made me realize I would like to continue studying the connections between Victorian literature (especially literature written by women) and the Risorgimento—it is in these connections that I believe I can continue to enrich my academic field.

That is to say, my days in Oxford were not without work and difficulty. Neither is Oxford a perfect institution, as many imagine it to be.

During the first few weeks of my first term at Oxford, I noted many shocking contrasts between how Oxford advertised itself and the realities of the city. Swaths of Gothic architecture, stained glass windows, stretches of old streets and stories; in the distance, if you look closely, you can almost see the pervading oxymorons that are present. Outside these great tall churchs and libraries, you can find the homeless begging for money or for their next meal—and if they’re lucky enough, they may own a tent as a place of refuge. It’s almost as if the ancient architecture looming over them is there to remind them that these establishments, which pride themselves on changing the world, will never help the very people right outside their own doors. I often wondered what Oxford did with their £1.3 billion endowment fund—individual colleges of the University have their own endowments, which amount to £5.06 billion, by the way. It frustrated me to see the university encourage collective action and progressive change amongst the students, but to see the locals suffering on the very same streets.

I also recognized my extreme privilege to be able to attend one of the greatest English-speaking universities in the world, especially because I came from city where for some, attending the local university was the most they could ever hope to achieve, due to personal circumstances. Columbus State University is the most diverse public university in Georgia, but Oxford felt like the complete opposite. The student body appeared to be, by a wide majority, white and financially privileged. Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised by that. As I step into the Radcliffe Camera to have access to books found nowhere else in the world, I am aware of the literal and metaphorical gates which prevent most of the world to do the same.

As I begin my last term at Oxford, the springtime flora, fauna, and weather forecast offers me yet another reminder of Brideshead. Waugh used the Latin phrase Et in Arcadia Ego (“Even in Arcadia, there am I”) for the first chapter of the novel to set off its beautifully poetic but admittedly Romantic beginnings in Oxford. Yes, I am living the academic’s delicious dream of being in Oxford. No, I am not quite drinking expensive wines and eating strawberries under a tree with Lord Sebastian Flyte. Yes, I am stressing over my 2,000 word essays due every week (and two of those due every other week). But the point of the motto is that Death is the one who says it. It is sort of a memento mori (“remember you will die”), but for a different usage. In other words, even in the happiest of times, in the loveliest of places, Et in Arcadia Ego reminds us that Death is never too far away. Hopefully, I will not die anytime soon, but the motto does remind me to both be appreciative and critical of my time at Oxford.

Et in Arcadia Ego, indeed.

Jessica is an English Literature graduate who minored in History. Jessica started working as a reporter for The Saber/The Uproar during her first semester...