Sexual Assault is Prevalent in the Military

What do you assume when you hear that a veteran has PTSD?

To outsiders, the military may look like its own society — one that intermingles with ours, and yet, becomes increasingly separate as a divide grows between it and mainstream American society.

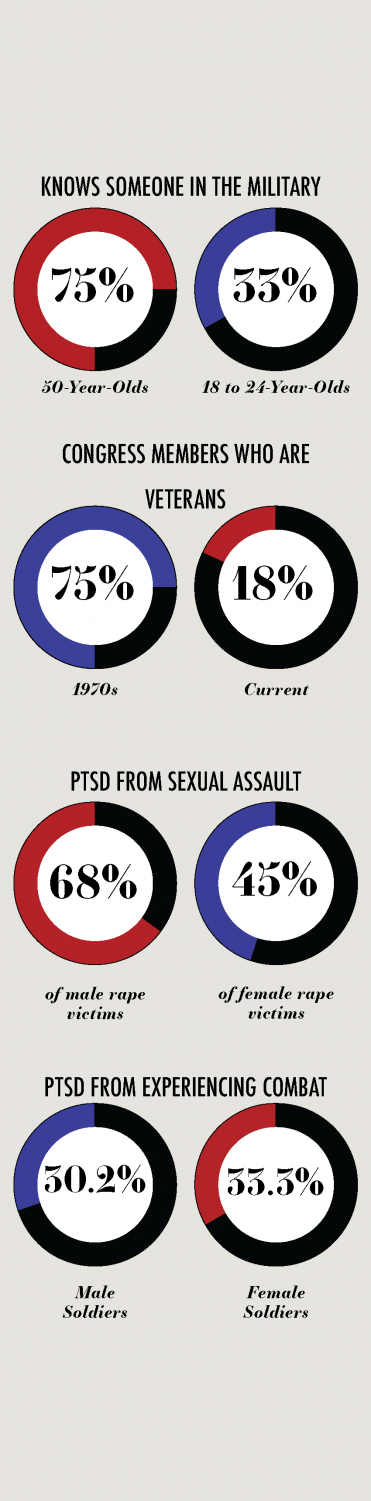

Half of American youth know very little about the military, a trend that is lowering recruitment, according to U.S. Army Recruiting Command. According to Pew Research Center, over 75% of adults over 50 have a close relative who is in the military, but only 33% of 18-29-year-olds do. In the late 1970s, about 75% of Congress members were veterans, whereas the percentage is now below 18%.

For service members who have undergone traumatic experiences in their careers, alienation can compound their suffering. War can be traumatic, but at least awareness of combat-related PTSD is growing.

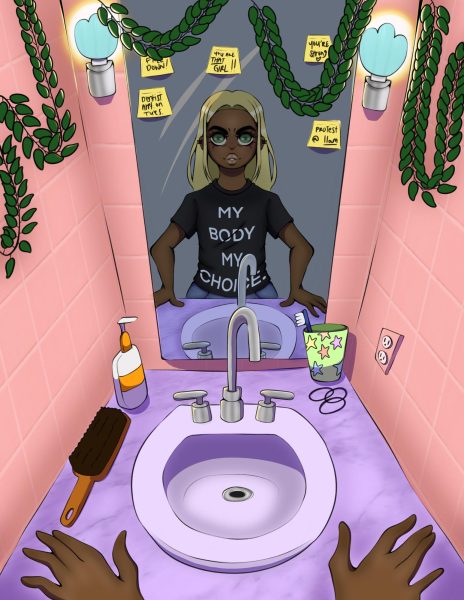

Another problem, however, lurks in the shadows of public awareness: Sometimes, service members encounter enemies wearing the same uniforms, sleeping in the same barracks, and eating in the same mess halls. The threat of sexual assault is much higher from fellow soldiers than it is from enemy combatants.

A classic illustration of veteran PTSD is one of a man going into a panic attack, interpreting fireworks as gunshots. But the “thousand-yard stare” associated with soldiers isn’t unique to combat trauma.

“For reasons not completely understood, more rape survivors develop PTSD than do combat-veterans,” states Faces of PTSD. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs reports that in a study, 45% of female rape victims had PTSD, which was higher than the 38.8% of male combat

trauma victims with PTSD. While 65% of male rape victims had PTSD, the percentage of male rape victims in the study was only 0.7% as opposed to 9.2% for female rape victims. This study didn’t include a percentage of female combat trauma victims with PTSD. In a separate study on U.S. Navy healthcare personnel, men who experienced two to three combat exposures had a PTSD rate of 30.2% whereas women who experienced two to three combat exposures had a rate of 33.3%.

On May 1, 2018, the U.S. Department of Defense released its Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military.

From fiscal years 2016 to 2017, the number of sexual assaults reported by service members grew by 10 percent. Over the past decade, sexual assaults against active duty women have been cut in half, and they’ve fallen by two-thirds for military men.

5,864 of the victims in fiscal 2017 were service members, but 868 of the victims were American civilians or foreign nationals, and 37 victims’ statuses weren’t available. Of the 5,277 victims assaulted while they were in the military, most of them — about three fourths — were women. In 2006, only one in 14 victims reported being sexually assaulted. By the time the DoD released its report, that figure changed to one in three.

About a quarter of female veterans report experiencing at least one sexual assault during their military service to the Department of Veterans Affairs, according to Battered Women’s Justice Project.

Only one percent of male veterans do the same. Female service members who are younger, of enlisted rank (as opposed to being officers), and who experienced sexual assault before joining the military are at an increased risk of experiencing it again in the military.

According to CSU instructors SFC Paul Casiano and LTC Carlos Lock, the military has programs to prevent and address sexual assault. “Our SHARP program — our Sexual Harassment And Response Prevention program — is designed to prevent sexual assault,” said Lock, who elaborated that SHARP deals not only with how to properly report sexual assaults but also promotes awareness of current trends.

“And we have multiple systems,” added Casiano. “It’s called I.A.M. — the intervene-act-motivate.” Casiano said that the program mission statement of I.A.M. is “awareness, prevention, training, education, victim advocacy, response, reporting, and accountability.” He said that CSU’s ROTC program recently conducted I.A.M. training, as did the military.

“We try to ensure that things like that don’t happen at all, or when they do happen, you know, take those measures as far as reporting and ensuring that everybody gets the required assistance that they need,” said Lock.

Despite decreasing sexual assault rates and programs such as SHARP and I.A.M., many say that military culture and structure prevent victims from getting the assistance and justice they need.

In addition to the usual reasons for not reporting sexual assault, such as fear of embarrassment, military victims face an additional obstacle: a thinner division between private life and work life, which makes secrets harder to keep.

“That creates fear that others will find out and that they will be perceived as weak and unable to accomplish the mission,” explains BWJP. “They fear this might affect promotion and assignment to good jobs or lead to separation from the military.”

Victims are allowed to make “restricted reports” that limit disclosure to specified individuals, such as sexual assault response coordinators. A victim choosing this route may forgo an official investigation and just receive care. An “unrestricted report” allows disclosure to unspecified individuals, including relevant officers and law enforcement. The commanding officer of the accused is allowed to take a number of different approaches to address the issue. This discretion provokes anxiety in victims, as officers often take inadequate actions or actions that appear to be retaliation.

The more alienated a group becomes from mainstream society, the more abstract it becomes in the public’s consciousness. Numerous stereotypes abound about military veterans — typically, the assumption is that he’s male and that he might have come out of the military physically fit, self-disciplined, and mature — a better person than before. Alternately, there’s the stereotypical homeless veteran who never developed skills for any other career.

In general, service members are said to be heroes and are thanked for their service, but it’s a cultural custom more than a reflection of independent thought. It’s normal to thank a service member for their service as soon as one sees their uniform; they are seen as service members first and individuals second — representatives of the military.

Each service member has a life story as complex as anyone else’s, and every human being has a need to be understood. No one should have to suffer trauma from sexual assault or combat alone. Problems of an institutional level tend to be difficult to solve, as is the case of sexual assault in the military. Spreading awareness is easier.