Two Men Changed Voting in Columbus Forever

The story of Primus King and Thomas Brewer’s legal battles for the right to vote

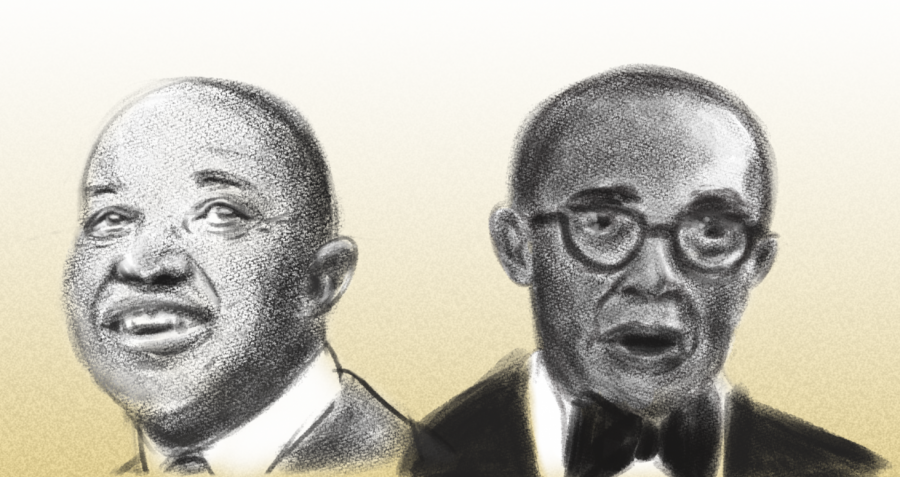

Illustration of Thomas Brewer and Primus King

In the 1940s, another movement was occurring that would eventually liberate the city and the South. Primus King, a Black Columbusite, challenged the all-white Democratic Party primary in 1944, and the federal courts ordered the integration of that election. In 1956, Thomas Brewer, a local leader of the civil rights movement, was shot and killed.

Brewer, a physician in Columbus, was active in the movement from the 1920s up until his assasinaion on Feb. 18, 1956. In 1920, he established his medical office on the 1000 block of First Avenue, as other Black doctors and dentists had done before him. As the strategist for the local NAACP, Brewer designated King, a Columbus barber and minister, to challenge the voting system by attempting to vote in the primary election at the courthouse in Muscogee County on July 4, 1944.

King was duly registered to vote in Georgia, but was roughly turned away by a law officer who escorted him back out to the street. By prearrangement, King then walked several blocks to the office of Oscar D. Smith, a white attorney, who prepared a lawsuit against members of the Muscoee County Democratic Party Executive Committee for denying his right, as a citizen of the United States, to vote.

On Oct. 12, 1945, Federal Judge T. Hoyt Davis ruled in King’s favor and awarded him $100 at 7% interest. Brewer and others in the NAACP raised $10,000 to support the campaign, and in March 1945, the state of Georgia abolished the $3 poll tax, thereby removing the economic barrier to voting. King’s almost two year struggle against the white primary finally eliminated the legal barriers that stood in the way of Black Georgians’ right to vote.

Following this victory, Brewer initiated successful Black voter registration drives in Columbus in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He also campaigned successfully for the hiring of Black police officers in Columbus in 1951. In 1955, Brewer created an effort to integrate the golf course on Columbus’s South Commons, and there were also allegations, which he denied, that he had used his influence to deny a popular white Columbus citizen the position of city postmaster.

These two issues raised local hostility towards Brewer, and he was shot and killed by Lucio Flowers. Flowers owned a clothing store under Brewer’s office and claimed to have shot Brewer in self-defense when Brewer, after a heated disagreement, entered his store and reached for a pistol. At the time, police and a grand jury accepted Flowers’s story.

The disagreement occurred when Brewer and Flowers witnessed the forceful arrest of a Black man by police. Brewer believed the arrest was an example of police brutality and wanted Flowers to be a witness, but Flowers refused, believing that the man was resisting arrest. Flowers had called for the police before any actual violence occurred, so an officer and two other men were in the store at the time of the shooting. As a result of this shooting, the Columbus civil rights movement followed a much less confrontational course of action into the late 50s and 60s.

Eventually, Primus King earned praise and recognition from the political establishment that had once rejected him. June 28, 1973 was proclaimed Primus E. King Day in Columbus. In 1977, the Democratic Executive Committee of Muscogee County paid King the $100 plus interest, $324.70, that they owed him. In 2000, Governor Roy Barnes signed a bill naming a stretch of state road in Columbus the “Primus King Highway.”

(She/her) Ashley is a theatre major who loves to focus on issues that concern the community of Columbus. She graduated from CSU in Spring 2021,