Out of the Classroom and Into the Coelacanths

Faculty member does international work with rare fish off the coast of Africa this summer

While some people spent their summer breaks at the beach, in the mountains, by the river, or simply at home, others spent it conducting and refining new research. Several professors and students at CSU have been busy progressing and finishing projects on various subjects, including one led by Michael Newbrey, Ph.D.

Newbrey, a biologist with a concentration in fish (otherwise known as icythyology), continued his research on coelacanths — a project which he has already been working on for two years. “Coelacanths were these type of fishes that were thought to be extinct until 1938 when we found some live ones off the coast of Africa,” Newbry said.

Because of heavy harvesting by fish markets in Africa, the fish are now critically endangered. “In an evolutionary sense, they’re going extinct,” he added. The fish, which have lobed pectoral and pelvic fins that strikingly resemble human hands and feet, are more related to tetrapods than other fish and have been around for over 400 million years.

“We’ve been studying them since 1938, and we still don’t know that much about them,” Newbrey said. He sought to change that through studying age of growth.

“If you’re going to conserve an endangered species, you need to know how long they’re going to live, how often they’re going to reproduce, and when they become sexually mature so that you can gain some kind of idea of how many offspring they’re going to have,” Newbrey said. In 1977, scientists published a paper on coelacanths that hypothesized that they only live to around 20 years. In 2000, another group of scientists analyzed the same set of data and proposed the hypothesis that they live to about 40 years. Even later, yet another team of scientists tackled the question of the average coelacanth lifespan and concluded that it was over 100 years due to their observations, which took place in submarines because of the depths at which coelacanths live, that coelacanths barely changed size in over 20 years.

Newbrey; Hugo Martin Abad, Ph.D., who is a visiting researcher from Spain; and undergraduate student Frances Woolfolk all collaborated on a project to determine whether these recent findings were credible or not. They examined specimens from various places in the world, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and a museum in Cuenca, Spain. The specimens at the AMNH were comprised of fossils over 100 million years old from South America and preserved coelacanths from off the coast of South Africa.

“The scales are very similar to other types of scales we’ve studied in fish,” Newbrey said. With that in mind, he decided to age them by counting the growth rings. “If you chop a tree down and count the rings on the stump,” he said, “you can kind of get an idea of the age of the tree. We do something really similar with the scales. We can count the growth rings on the scales to ascertain their age.”

After gathering data on the scales from the museum and comparing them to data from previous research on live specimens, Newbrey noticed that coelacanths grow very slowly and that even small ones can live up to 48 years. “Our support is for the 100 year hypothesis or maybe something in-between the 50 and 100 years.”

As for the results of the project, Newbrey said that the research has international implications for how the species is managed. “Our study would suggest that it’s probably in the teens that they become sexually mature,” he said about the coelacanths, bringing attention to the issue with population growth. With the harvesting in South Africa, the species is still at a sharp decline, and because coelacanths take so long to produce young, their population isn’t rising at a comfortable level, either. “We need to be extra careful in particular (with managing them)… They don’t produce many pups or offspring, and it takes two years for them to mature inside the mom.” With more research, scientists could prevent further harvesting and could allow the population to return to a healthy number.

Even with the project’s successes, there were a few obstacles. Two of these were issues with interpreting data and with gaining access to specimens in museums. With the data from previous research, the lines were all over the place as a result of errors in scale aging. Even when Newbrey, Abad, and accounting major Frances Woolfolk worked together to assess the scales, they found that years of research and hundreds of hours of studying did not eliminate all of their challenges; there were other marks on the scales in addition to growth rings. Distinguishing the two became an art.

Aside from complications with aging the scales, Newbrey and the others encountered problems with procuring samples, especially from a museum in France that denied them access because other research groups had inspected the specimens before. Because there are very few museums with coelacanth collections, the museums that do have them are notably protective. “It’s hard to find a museum that will work with you,” Newbrey said. He continued, “It’s hard to gain access to the specimens. It’s hard to have enough money to access the specimens.”

As of now, the first international research paper, which covered the morphology of the scales (e.g., their shape and surface details), has been published, and Woolfolk presented the findings at the Association of Southeastern Biologists’ meeting in March and at Tower Day in April. Newbrey is looking to publish a second manuscript and possibly even a third on the age of growth. He also hopes to send Woolfolk to Britain this December for another presentation.

But the research doesn’t end there. Newbrey plans to head in a new direction with the study– that is, studying new species in Spain. “If we can understand how ancient species grew–their age of growth and biology,” Newbrey said, “we can understand more about the effect of climate change on them… We might be able to discover how coelacanths respond to climate change today.”

In addition to furthering his research on coelacanths, Newbrey is carrying out another project, which he has entitled the “Chattahoochee Fish Project.” This one, which studies the fish from creeks feeding into the Chattahoochee and the bass from the river itself, focuses on intersex fish. So far, around 16 people — professors and students alike — are assisting with the project. With more time and work, Newbry expects to use science to benefit the fish populations at home and abroad.

____________________________________

Q&A with Frances Woolfolk:

What year are you?

I am a senior, and I graduate in December.

How do you feel about working on the coelacanth project with Dr. Newbrey?

It’s important in understanding the evolution of a species for a number of reasons. Studying a species (including ancient relatives of the species) can help us understand the biodiversity we have in the world, how healthy an ecosystem is, and if an ecosystem is thriving from the level of its biodiversity.

What drew you to the project? What piqued your interest?

I’ve always been fascinated with marine biology since I was a child. When I took the Honors Biology course (study of fisheries), it expanded my knowledge and appreciation for marine life. In today’s world, we have many problems and threats facing species that add to our world’s biodiversity. This project is very special and unique to me. The two extant coelacanth species left are critically endangered. There is not a lot of published literature on coelacanth age and growth. Age and growth data is one of the important factors that can help us determine how to prevent further overall degradation of the species, and it can help give us a better understanding on how to help. I am extremely excited to help blossom this project into international research, and I am very honored to be a part of it.

What do you think will ultimately come of the research?

I believe a better understanding of how we age and understand coelacanths will come from this project.

Could you please give a summary of the work that you’ve done so far?

In preparation, I spent the summer of 2017 aging and examining scales of a somewhat similar fish (in regards to scale similarity). I prepped myself in examining the research that existed on coelacanth history, coelacanth biology, and any knowledge that would be found incredibly useful for our trip to the American Museum of Natural History in January of 2018.

What is a fun fact about yourself?

I practice circus arts (aerial hoop).

____________________________________

A Fishy Encounter

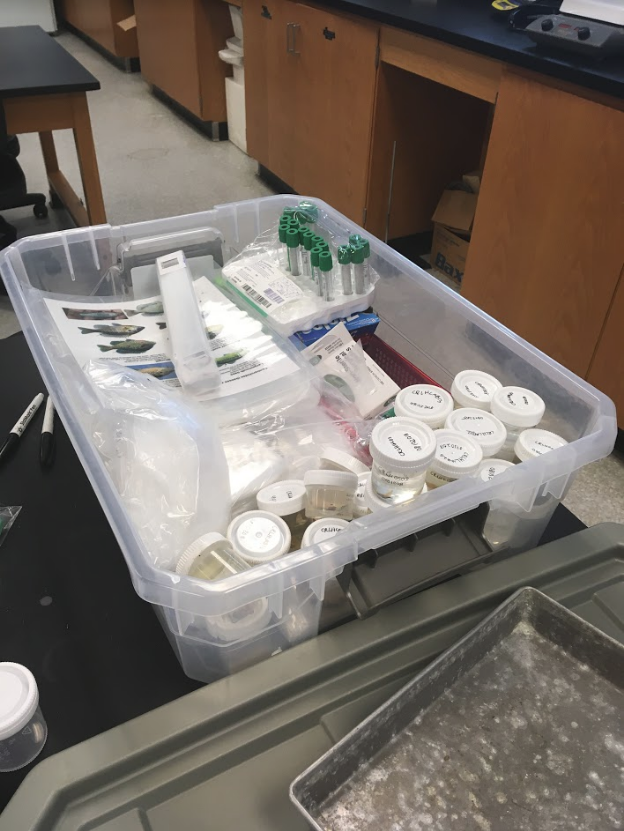

Fish dissections for the Chattahoochee Fish Project

Within Room 255 in LeNoir Hall, there arose the nose-pinching smell of river water. The suspected cause? Two coolers filled with Chattahoochee spotted bass, smallmouth bass, and gizzard shads.

It was Friday. While this may not mean much to the average person, to the students and faculty in Room 255, it meant dissection day. As a part of Dr. Newbrey’s work with the Chattahoochee Fish Project, he, other professors, and students all carry out dissections on the fish that they collect in the morning from the Chattahoochee. This project, which is still ongoing, aims to determine the potential presence of intersex conditions, such as female gonadal tissue (or eggs) growing on male gonadal tissue (or testes) in male fish from the river. Previously, Newbrey had tested this with fish from nearby ponds, and due to the evidence of intersex conditions in some of the fish, the project served as inspiration for this one.

The intention behind dissection is to later examine the gonads of the fish for intersex conditions, as well as to examine other organs for information such as age of growth and water health, including any water toxicity. As Mrs. Elizabeth Klar put it, “The fish tell a story for sure.”