Black Heritage in Columbus

Exploring Black Heritage in Columbus

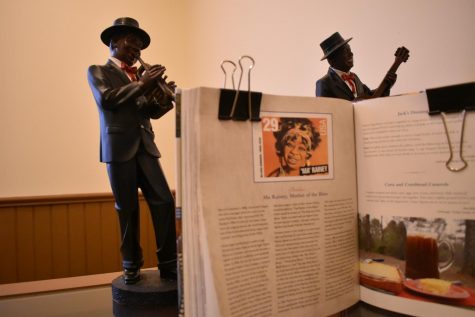

Gertrude Pridgett “Ma” Rainey:

The home of “Ma” Rainey, located at 805 Fifth Avenue, was reconstructed and returned to its glory in 1997. It now serves the city of Columbus as a free museum with personal tours offered Tuesday through Saturday. In 1991, when the city bought the home for just $5,000, it was in poor condition due to years of neglect. After a long road of fundraising — with BB King playing in a benefit concert to help fund the project in 1997 — the project began to gain momentum. After a large grant offered by the Save America’s Treasures initiative, the project was finally able to move forward, transforming the home into a museum that could better honor the “Mother of Blues.”

Rainey was born and raised in Columbus, GA, where she became interested in the entertainment business at a young age, performing in talent shows as young as 12 years old. Rainey, as described in the informational pamphlet provided to museum goers, “was a short, plump, dark, and flashy [woman]. She wore diamonds in her ears, around her neck, in her headbands and [on] her fingers. She wore necklaces of $20.00 gold pieces. Her dresses were embroidered with rhinestones and sequins.” And as described in an article in the New York Times in 2008, “She was a whiskey-slugging contralto with raunchy songs, a sound business sense and bisexual tastes.”

Rainey started out on her own working the minstrel circuit, until she met William “Pa” Rainey, who would become her husband and business partner. The couple traveled the country performing their minstrel circuit act all over. About 12 years after their marriage, in 1916, the couple separated, and “Pa” Rainey fell off into the background as “Ma” Rainey’s fame only grew, becoming “Madame Gertrude Ma Rainey.”

She performed various forms of comedy, dance, and song as her act. By 1917 Rainey had become so popular that she was selling out integrated shows, an unusual occurrence for the time. In December 1923, Rainey’s fame brought her from the minstrel circuit to the recording booth where she would go on to record 92 songs, at least a third of which she composed herself or collaborated on, even despite the fact that she could not read or write. Rainey would come to her sessions with drawings of what she had in her mind or what would remind her of the lyrics she composed, where she would have someone put the words and music to paper for her.

Rainey was known for holding nothing back when it came to her lyrics which typically addressed “abandonment of her man, prostitution, lesbianism, sado-masochism, drunkenness, superstition, and murder,” according to the museum’s pamphlet.

As the decade changed from the 20’s to 30’s, so did the style. Jazz and Swing was becoming more popular, with a new younger crowd coming in. Rainey was said to be set in her style and unwilling to change. Her contract with Paramount Records was canceled. Rainey returned to her roots in the minstrel circuit for a few years, and then in 1935 she retired her career in the entertainment business and moved back to her hometown in Columbus where she lived in her home with her brother until she died in 1939 of heart failure at 53 years old.

Rainey was inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 1983, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990, the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 1992, and the Georgia Women of Achievement Hall of Fame in 1993. Rainey also was recognized by the Postal Service with a stamp in 1994 to honor her achievements.

Notable lyrics of Rainey:

From Prove it on Me – “I went out last night with a crowd of my friends, it must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men. Wear my clothes just like a fan, talk to the gals just like any old man.”

From Black Eye Blues – Take all my money, blacken both of my eyes, Give it to another woman come home and tell me lies. You low-down alligator, just watch me soon or later.”

From See See Rider Blues – “I’m so unhappy, I feel so blue. I always feel so sad, I made a mistake. Right from the start, oh, it seems so hard to part.”

Liberty Theatre:

The Liberty Theatre originally opened in 1924; it served as a segregated theatre and later a segregated movie theatre, sharing entertainment with the African American community of Columbus. Famed performers such as “Ma” Rainey and Cab Calloway frequented the historical theatre in its early years. The doors of the business were closed after a decline due to integration in the 70’s; however, thanks to funding and grants, the theatre was expanded and re-opened in 1996. Several plays have come into production in recent years, and events are hosted regularly as well as the offer of venue rentals. The theatre stands today and serves as an active part of the Columbus community as well as a historical location.

Dr. Thomas H. Brewer:

Dr. Thomas H. Brewer (1894-1956) was a Selma University graduate, a physician, and a civil rights activist. Brewer moved to Columbus in 1920 and opened his own office at 1025 First Avenue where he shared a building with a clothing store owner, Luico Flowers. In Brewer’s years in Columbus, he led as a founder in the establishment of the NAACP Columbus Chapter, and most famously supported Primus King in the King V. Chapman legal case. Brewer contributed and helped raise funds in support of King and his right to vote. The case eventually led to a win for King and a win for voter’s rights. Brewer additionally was a vocal advocate of integration of schools as well as other local areas, raising tensions for him locally. Brewer was shot seven times and killed outside of his business following a dispute with his building neighbor, Flowers, who claimed self defense. 2,500 people came to mourn his death at the First African Baptist Church on Fifth Avenue.

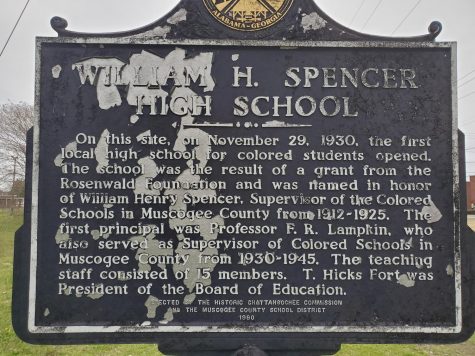

Spencer High School:

On November 29, 1930, the first high school for African American students in the Columbus area opened up its doors to the African American community. The school began through funding from a Rosenwald Foundation grant. The school was named in honor of William H. Spencer, Supervisor of the Colored Schools in Muscogee County. The small high school held a teaching staff of 15 teachers and Professor F.R. Lampkin served as their principal for fifteen years from 1930-1945.

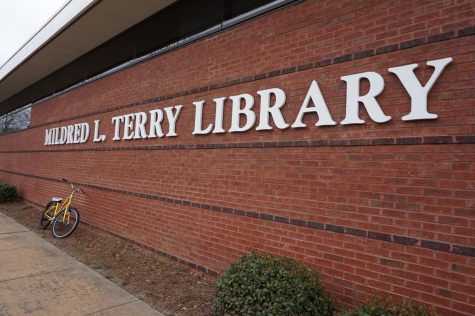

Mildred L. Terry Library:

The creation of the first public library for African Americans in Columbus was prompted due to segregation and denial of access to a new public library in town. The library was opened on January 5, 1953, and was later named in 1981 after its first librarian, Mildred L. Terry.

1828 Cemetery for Interment of Blacks:

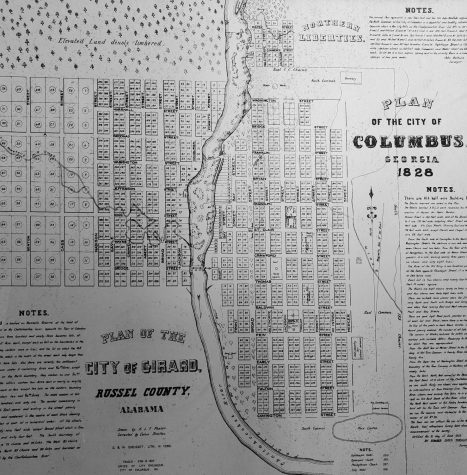

This location, known as the “old slave cemetery,” is located at the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Sixth Street. It was established in 1828 and served as burial grounds for African Americans until 1836 when the first grave was dated at the Porterdale cemetery. The land was eventually built over with railroad tracks, covering the history of the site. In recent years it was re-established by the city as a historical site and resting ground after the city council approved a $24,000 budget for an archeological survey, according to an article from WTVM News Leader 9, in 2010. In 2014, the city unveiled the renovation of the site as a garden that includes a walking path, benches, and informational placards, as reported by the Ledger Enquirer. As of today, the site is still intact, and the history remains; however, the informational placards serve as no more than empty canvases due to wear from the elements over time. The main informational placard outside of the garden prevails, offering guests a brief history as well as the original plans for the town of Columbus. “The identity and numbers of those buried on this site remain unknown,” as stated on the main placard.

Porterdale Cemetery:

Porterdale Cemetery is the oldest of the three in the conjunction of cemeteries with the neighboring Riverdale and East Porterdale Cemeteries. Porterdale can be found on the west side of Tenth Avenue, intersecting with Victory Drive. The cemetery is comprised of mostly African Americans, and is the resting place of many prominent African American figures in the Columbus community. Porterdale Cemetery is designated as an area for burials on the earliest — established in 1828 — Columbus Frontier map. The earliest marked grave; however, dates back to 1836. The cemetery holds a large number of unmarked graves of which dated back to an “oral tradition,” leaving their history lost over time, according to the cemetery’s website. This cemetery holds the resting place of black historical figures such as; Lizzie Mae Lunsford, William H. Spencer, and Gertrude Pridgett “Ma” Rainey.

The locations portrayed in this article are available to the public and welcome explorers. The Columbus Visitors Bureau offers a “Black Heritage Trail” that highlights these sites and many more; however, the trail itself is not conducive or practical for a self guided tour. In contrast, the Columbus based tour company, Vicinity Tours offers a Black Heritage tour among others. Victor Feliciano, owner and operator of the tour company, commented that while the trail was great in context, “no one carried the torch” for the project after the death of its original organizer, Judith Grant. Feliciano hopes to offer his tour as an alternative, also highlighting some of the locations along the trail, as well as a few more in addition.

Paige is a reporter with the Saber at CSU and a senior English major. Her track is creative writing, so she didn't expect to find herself loving to learn...

Stephney Doucet • Feb 27, 2020 at 11:20 pm

Great article! Very informative!