CSU Theatre students speak up about experiences of racism within their department

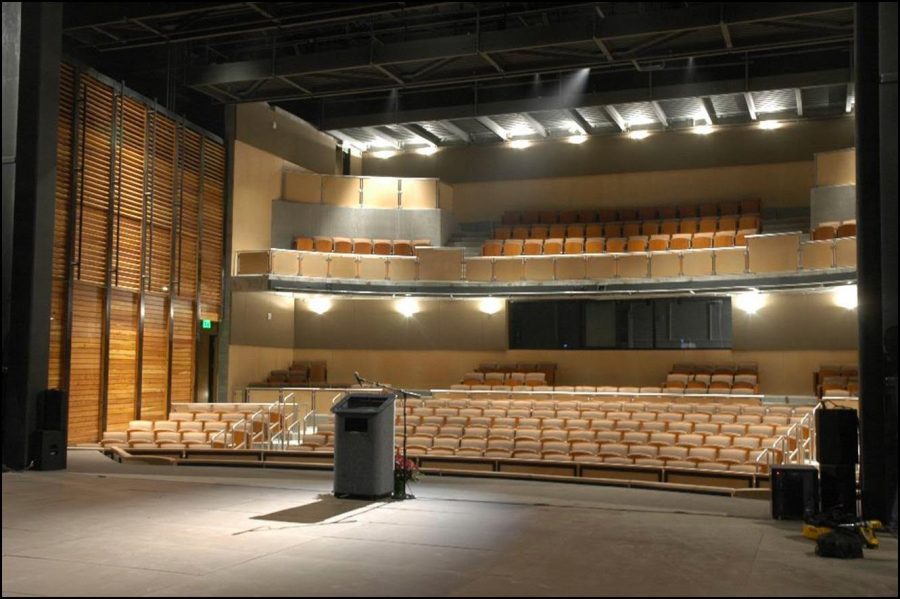

On June 1, 2020, CSU Theatre Department Chair and Professor Dr. Larry Dooley reached out to students and faculty to begin a discussion about issues of race and color within the department. Students quickly responded, sharing their experiences of racial discrimination and/or harassment with theatre department faculty.

“There’s always been an issue of racism in our department,” said Alexia Shepherd, a black American BA Theatre Arts senior. “The very first thing I noticed when I came here was that they didn’t hire our black professor Jamila Turner. She had been working there for a few years, but she still wasn’t full-time.”

Only two out of 18 members of the department are black Americans, according to the CSU Theatre Department Faculty and Staff page. Those two are Box Office Manager David McCray and part-time faculty member Elizabeth Reeves. McCray’s picture is not displayed on the faculty page.

Shepherd explained that three professors within the department had continuously made racist comments throughout her time at CSU: Brenda Ito, Steven Graver, and Kimberley Garcia.

“Every year, Steve [Graver] will pull out the makeup kits and say ‘the African-American colors always make me so hungry. You know, it’s something like “almond” or “chocolate.”’ I don’t think he’s ever gotten a laugh from it.”

During one makeup class with Graver, Shepherd recalled that the professor asked the students to help him demonstrate different types of looks, such as old age. Shepherd raised her hand, offering to demonstrate old-age makeup on her skin. Graver then said he was going to use two people to demonstrate the look on two skin tones, even though he wasn’t doing that for any other look.

Shepherd then recalled some comments said by Garcia. Shepherd stated that Garcia would always record black hair types as “nappy” or kinky.” During CSU’s production of “Corduroy,” Shepherd told Garcia that she required a size nine shoe. Shepherd also told Garcia that she had flat feet, and Garcia responded, “Oh, the great African-American curse.”

“I’ve been at CSU since 2015. When I got there, I was told that [black people] would have to stick together,” said black American senior Sulaiman As-Salaam, who is a BFA Design/Tech major with a focus in Lighting Design. “That was when I realized this is something that I had to deal with.”

As-Salaam spent most of his time at CSU as a technician, but he decided to audition for a show one year. During callbacks, Ito told As-Salaam that his name was “too complicated to learn,” and watched his name “butchered so terribly.”

“It was appalling, said As-Salaam. “So I left in 2018-19 for an internship across the country because I couldn’t take it anymore. I wasn’t planning on coming back to CSU.”

As-Salaam wasn’t the only student whose professors refused to correctly pronounce their name. Mielan Barnes, who graduated Spring 2020 with a BA in performance, recalled that Graver would refuse to learn her name during a makeup class.

“I’ve been at that school for four years, but they refused to learn my name,” said Barnes. “He would call me ‘Mee-lan,’ or ‘Mylin,’ and I would tell him that’s not my name.” Barnes then proceeded to tell Graver how to pronounce her name correctly, but Graver claimed that was how he was pronouncing it. “It’s not a difficult name,” Barnes expressed. Then Barnes recounted that Graver also refused to pronounce another black student named Jarell (pronounced “Jah-RELL). Graver instead pronounced the student’s name as “Jair-uhl” for the entire semester.

“There was a time where we didn’t have names,” said Barnes. “There was a time where my ancestors came here and were told to be called something else. So I believe that everyone who wants to be called something, whether it be pronouns or name, that’s their right, and that’s their identity. And so if you strip away my right and my identity, then who am I?”

These three students also spoke up about the lack of colorblind casting in CSU shows—meaning that if a character’s race is not crucial to their character, then that role is open to actors of any skin tone. The students also noted a tendency of CSU Theatre to typecast black actors into stereotypical black roles. For example, during the summer of 2017, CSU Theatre was preparing to cast for the children’s play “Freckleface Strawberry.” The play is about a young white girl with red hair and freckles who was picked on and treated differently because of her appearance.

“The only black person who was cast in that show was a black boy stereotyped as a basketball player,” said Barnes. “They needed a basketball player who was also like a rapper slash thug that fit the storyline. And so they cast one black man.”

“I was called back for the mother of Freckleface, and I was not cast,” continued Barnes. “I thought I did a great job at the callback.” Barnes believes her skin color was the reason she was not cast.

Later that summer, CSU Theatre planned to produce the children’s play “Jack and the Wonder Beans.” Brenda Ito directed the production. When Barnes auditioned for a role in the show and made it to the callbacks, she noticed that there were only two black people there. Ito told Barnes that if Barnes didn’t make the cast list, it was because Ito already bought the costumes for the show. Barnes didn’t understand why she was called back to the show.

“When people tell me conversations with [Ito’s] assistant directors or even her stage managers,” continued Barnes, “they tell me that she has told them that we have to call at least two or three black people back. ‘So they don’t riot or so they don’t revolt.’”

Barnes began to wonder if she had chosen the wrong craft. She said: “I got depressed, and so I took a year off school because theatre was something so important to me. I came back, and I know I am talented and worthy.”

Barnes recalled that she was cast as a mammy character in the Fall 2018 production of “The Children’s Hour,” a 1930s play written by Lillian Hellmen. “I would prefer not to be playing a maid in the 30s,” said Barnes. “But [the director Molly Claassen] had a history of casting that way even though she prides herself in colorblind casting. Colorblind casting has to be intentional.”

In the Fall of 2019, CSU produced the show “Peter and the Starcatcher” which is a prequel of sorts to “Peter Pan” that takes place in late Victorian England. “When [the department] chose that show, they said it was going to show diversity,” said Alexia Shepherd. “The only black person in that show played a prisoner” who wore a bag on his head when he entered the stage.

“They tell us they’ll colorblind cast, but then we do a show with 30 people and they pick three [people of color],” said As-Salaam. “None of them are title roles.”

“I felt so concerned about my other students who had to sit there and wait for their good chances, for the black show to come around,” said As-Salaam.

When As-Salaam came back from his internship in 2019, he made plans to try to improve the theatre department after noticing a “massive influx of students of color” that year. He realized that almost half of the department now consisted of people of color. As-Salaam reached out to many of his fellow students and created a petition to make a list of demands from the CSU Theatre Department. It requested non-caricature roles for POC, courses that have student diversity in mind, an environment where students could bring up insensitive comments from faculty members, and representation in the theatre department staff. The petition received over 180 signatures.

As-Salaam then spoke with Theatre Department Chair and Professor Larry Dooley, presenting him the petition and its demands. Dooley assured As-Salaam that students would be able to have a town hall to address all of students’ concerns. He also said he would attempt to bring in a masterclass for specific black and POC skills.

“Things never progressed,” said As-Salaam. “They kept saying that they were talking about it in their meetings.” Then, the theatre department chose the show “Milk Like Sugar.”

Barnes described the play’s plot: Three teenage girls make a pregnancy pact so that they can live off of government housing and WIC. The plot of the play made Barnes very uncomfortable, as she felt that it confirmed “every negative stereotype about blacks.” She tried to speak to Associate Professor David Turner about her concerns, but Turner felt like it was “somebody’s story.” Barnes eventually decided not to audition for the show because “it went against [her] morals and values as a black woman.”

CSU Theatre asked Springer Opera House Education Coordinator Beth Reeves to direct the show because the only professor of color had left the department. Eventually, Reeves accepted the position and asked Barnes to audition even though she wasn’t planning to. Because Barnes did not originally intend to audition, she had not filled out an audition form. Barnes didn’t think that would be a problem because CSU Theatre has casted people who didn’t originally plan to audition before.

However, Barnes recalled that Brenda Ito suspected her of sneaking in the audition through the back door. “The back door comment was triggering for me,” said Barnes. “I’m sure people are aware of black people having to go in through the back door because of Jim Crow, so it felt like a microaggression. Why would I try to sneak through the back door? Because I’m black?”

When Larry Dooley reached out to CSU Theatre faculty and staff to open the conversation on issues concerning race and color, he received a tremendous number of responses. Barnes noted that at one point during the email chain, Dooley requested students not to “call [faculty members] racist.” According to Barnes and other students, Dooley asked students included in the email thread to be more formal than social media or that he might stop reading responses. Many students felt this was a threat to conclude the discourse prematurely. Steven Graver responded that Dooley needed to listen to students.

The Saber conducted a Zoom interview with Dooley to discuss these issues within the department. Dooley stated that “there are some practices in the theatre department that kind of limit their ability to participate or make them feel uncomfortable.”

Dooley felt that this had been a problem within the department “forever,” but that it became much more apparent within the last couple of years. Dooley spoke about a number of solutions to try to eliminate the racial disparities within the department. Firstly, Dooley explained that the theatre department needed better communication. One of the ideas Dooley had to open up communication between the students and faculty was to create a student advisory board. Dooley explained that the board would consist of a group that would meet with him regularly to discuss student concerns.

Traditionally, the faculty committees within the theatre department choose the season’s shows for that year and reveal it to the students at the beginning of the year. Dooley recognized the need to make the season selection process “a much more transparent exercise.”

“One of the reasons we’ve been hired is because we have expertise and what is going to be educationally beneficial,” said Dooley. “And that doesn’t mean we know everything. It just means that we have a lot of experience with this, but we’re well aware that we’re going to have blinders on about certain things. So we need input. We need lots and lots of input. We need to listen very carefully.”

Dooley explained that the theatre department aims for a variety of shows: “We like to think by the time a student graduates…they should have experienced a good variety of shows, everything from classical theater, musical, non-musical, really new work, cutting edge work, socially relevant works, crowd favorites, and really off-the-beaten-path type of things.”

Dooley also noted that the theatre department needs to make sure their casting is diverse, in both gender and race. “We really want to look at our casting procedures,” he said. “We try to open it up and make sure more people get opportunity.” Dooley added that the department plans to keep track of its practices and how many people of color are being cast into shows.

Dooley also mentioned that he “deserved” all of the “heat” he has taken on the town hall that failed to happen. “I didn’t do anything about it over the fall break or winter break,” said Dooley. “My usual practice is to go to the faculty to bring it up to a meeting. There were some concerns that students would accuse other students…[and] faculty of things, and that the faculty would overreact.” Dooley explained the need for a moderator and said that the theatre faculty had come up with two choices for one.

“I wish I’d moved faster,” said Dooley. “Our attention [turned] to all things COVID. ‘How are we going to teach theatre online?’” Dooley expressed that he regrets not sending an email saying that the department would be unable to have a town hall, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Dooley offered a solution of having small-group Zoom meetings for students to discuss their concerns.

The Saber asked Dooley how the theatre faculty and staff would tackle diversity when none of their full-time faculty members are people of color. “We’re diverse in other ways,” said Dooley. “We’re not racially diverse.” Then, Dooley noted that the faculty consisted of both males and females.

Dooley explained the difficulty behind creating a racially diverse faculty was that the theatre department rarely gets new positions. “With all of the budget cuts, we’re actually a little concerned we may lose a position,” said Dooley.

When the theatre department is able to fill a new, open position, they are required to do a national search and advertise the position, according to Dooley. The search committee tries to “keep [their] eyes open for a diverse candidate,” but Dooley noted that “it’s rare that [the theatre department] even has somebody [racially diverse] that has applied.”

Dooley explained that few students of color in PhD programs exist in specific areas of study, such as theatre history. “There are far fewer qualified individuals out there in the marketplace,” said Dooley. “The Columbus State Theatre Department is competing with theatre departments all over the country for a very limited pool of candidates.

This is a generation coming of age in a world where things are on fire. Things that I think people of my age thought were going to get better from what it was when I grew up,” said Dooley. “Students are hurting, and they’re stepping out into a world where the economy is devastated by pandemic, and there’s violence and protests in the streets.”

“I hope they [the theatre students] know that. I hope they know that the faculty is hurting,” Dooley continued. “We’re having to do some really touch analysis and introspection.”

On June 5, 2020, As-Salaam accepted the position as coordinator and first member of the theatre department’s Student Advisory Board via email to the theatre students and faculty. In his email, As-Salaam included details about the process to apply to the committee and noted that the committee would be racially, sexually, and gender diverse. Additionally, As-Salaam noted that the committee would “work hand in hand with both the student body and faculty to make sure that the changes necessary to ensure our collective growth come to pass.”

Students that experience discrimination during CSU programs or activity on basis of race or color can contact the Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Office at 706-507-8920. More information on reporting discrimination at CSU can be found on the Academic Affairs website.

Update: The faculty accused in this article have been reached out to for commentary. The Saber is currently awaiting their response.

Jessica is an English Literature graduate who minored in History. Jessica started working as a reporter for The Saber/The Uproar during her first semester...

Nequia • Jun 11, 2020 at 1:56 pm

CSU is racist in itself so I’m sure they support this madness.

E • Jun 10, 2020 at 9:36 pm

Thank you for the article. First Saber article I’ve ever read. Thank you.